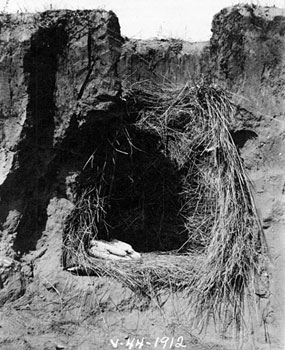

Model of a cache pit SHSND# 0086-437The efforts of the federal Indian agents were supported by Christian missionaries. The Hall mission school was a model farm and home. Here, pupils learned “. . . how to farm and garden in a profitable way.” (quoted in Independence, p. 149)

In taking up farming, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara knew they were depending on undependable weather and soil. The high land where their farms were established was too dry and their income now depended on forces they could not control: rain, heat, wind. When their crops were sufficient, they could sell them at Hebron. (Independence, p. 187, 201-202)

In 1894, the Hidatsa and other residents of Fort Berthold were assigned parcels of land (160 acres or less) under the Dawes Act. Allotment, as this process was called, gave ownership of land in fee simple (eventually) to Indian farmers, but the land was not always suitable for gardens. (Hidatsa, p. 80)

Though allotment tended to separate women from their traditional garden lands, there is strong evidence that women continued to garden for their families, using bottomlands when possible, but also gardening near their homes. Mercy Walker remembered her mother gardening probably early in the twentieth century, and Buffalo Bird Woman continued traditional garden practices including singing to the corn, though she felt that the traditions were being neglected by most gardeners. (Independence, p. 312, 314)